“Who are these atheists, anyway?” is the fourth and final part in the Atheism is not all it’s cracked up to be series by Gavan O’ Farrell, who works as a public sector lawyer.

Part one can be read here: Reason and Evidence

Part two can be read here: Morality and the Human Being

Part three can be read here: I don’t want it, so it isn’t there!

“Who are these atheists, anyway?”

This final Part on the series on atheism is less concerned with argument and more focused on who we’re talking about (and to).

“Non-theists” vary

I’ve decided now to refer to “non-theists”, as non-belief in God ranges from frank atheism (“There is no God”) to agnosticism (“I don’t know”) with each position having its own spectrum and labels not being applied consistently. Non-theists sometimes describe themselves as “rationalists”, “realists”, “sceptics”, “humanists” or “secularists”. However, they all reside in the “empiricist box” (see Part 1).

I’ve decided now to refer to “non-theists”, as non-belief in God ranges from frank atheism (“There is no God”) to agnosticism (“I don’t know”) with each position having its own spectrum and labels not being applied consistently. Non-theists sometimes describe themselves as “rationalists”, “realists”, “sceptics”, “humanists” or “secularists”. However, they all reside in the “empiricist box” (see Part 1).

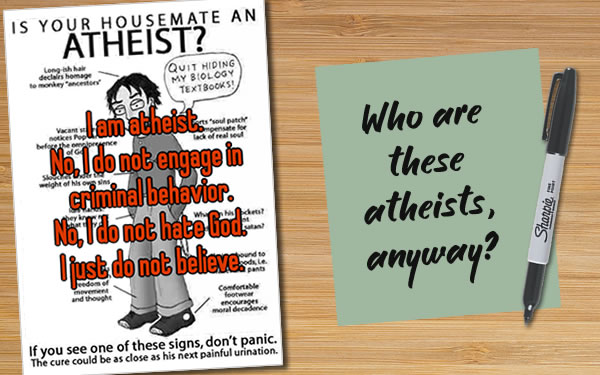

Needless to say, non-theists vary because they are human beings with myriad characteristics and experiences. I can mention some.

The most serious non-theists are those atheists who are intellectually attached to the evidence argument: if there were a God, it would have been proved by now. Their demeanour varies: some triumphalist and rude, some civil.

Ordinarily, atheists are a smallish subset of non-theists but, in this era of maximum self-expression, the number is probably artificially inflated.

The most visible non-theists are those who have a strong dislike of religion, especially Christianity.

This dislike may arise from their understanding of the general and historical conduct of the Church – sometimes a genuine misunderstanding that can be treated with information.

Illumination is not effective when the misunderstanding is deliberate – due to prejudice or even organised enmity. Socialists, for example, oppose Christianity as a matter of ideology, will contradict and abuse it at every opportunity and intend to bring it down. This stance can be found in many places, people and discussions: it doesn’t always call itself Socialism but, on the other hand, the Socialism brand is being laundered and relaunched despite its appallingly murderous history.

Or the dislike may be the result of bad experiences within the Church – a story which needs to be seriously listened to before mentioning “babies and bathwater”. Many are angry: mere indignation for some, while for others it is real hurt.

This anger is sometimes directed at God, not at religion. If a believer is angry with God, and doesn’t address the situation properly, the anger can take them far away – eg I might “punish God” by proclaiming that I don’t believe in Him.

Determined personal sovereignty and autonomy is another path to non-theism: “I don’t need a God to feel significant or secure”. Or, “I’m very clever and educated, I’ll take it from here”. Or simply, “No-one’s the boss of me!” More attitude than rationale.

Others were raised as non-theists and, like some Christians, think habitually and speak by rote.

Some non-theists call themselves “sceptics”, but I have found that they are typically half-sceptics – sceptical about God and the supernatural but not about their own claims about rationality and evidence (or the social and moral positions put forward by the Left).

Most non-theists are agnostics. This position is more understandable than a dogmatic “Ain’t no God”.

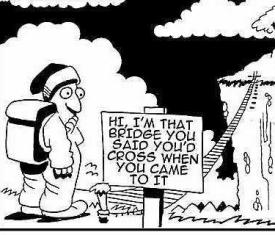

On the other hand, “I don’t know” is often a cover for “I don’t care”. It seems strange not to care that there might be Someone who made the cosmos and is in touch with humanity, but we continue to hear “I’ll cross that bridge when I get to it”.

On the other hand, “I don’t know” is often a cover for “I don’t care”. It seems strange not to care that there might be Someone who made the cosmos and is in touch with humanity, but we continue to hear “I’ll cross that bridge when I get to it”.

For some, “I’ll cross that bridge” is another pretext for avoiding a difficult issue. We should recognise that delaying consideration (and the “risk” of believing) is understandable, just like not wanting God to exist.

Some people prefer agnosticism because they believe it can accommodate spirituality. (Oddly, even some atheists are into this.) Of course, this “spirituality” falls short of belief in a God who is a Person – especially, a Person with, shall we say, “strong opinions” (who needs that?!). I think they’re trying to have their cake and eat it:

- A yearning for “the spiritual” is extremely common and entirely natural (a hint at the real yearning for God).

- However, with no connection with God or the supernatural, “spirituality” is just a species of strong emotion.

- True atheism – “truth is about reason and evidence” – is hard to market. No-one wants to think of themselves as a left hemisphere on a stick, so no wonder non-theist advocates use hard-sell. Enhancing non-theism with “spirituality” is smart marketing, but that’s all it is.

At risk of stating the obvious, a conversation with a non-theist is not a conversation with the embodiment of some ideas but with a fabulously complex and unique human being who is in God’s image and likeness, is loved by God, is in humanity’s shared predicament and has an irrefutable claim on everyone’s love.

At risk of stating the obvious, a conversation with a non-theist is not a conversation with the embodiment of some ideas but with a fabulously complex and unique human being who is in God’s image and likeness, is loved by God, is in humanity’s shared predicament and has an irrefutable claim on everyone’s love.

Atheism and politics

Visiting an atheist site, I once asked “Are there any conservative atheists or are you all Lefties?”. I was told, “If you’re smart enough to be an atheist, you’re probably smart enough to be progressive”.

Like much of academia, the media, the education system,much of government and parts of the Church, popular non-theism seems to have been infiltrated and largely taken over by “progressives” – to be politically allied with third-wave feminism, the LGBTIQ lobby and other “diversity” lobbies, and united with these in protecting Islam from criticism.

It is strange that such independent thinkers (a claim which non-theists often make to distinguish themselves from Christians) should all of a sudden be of one mind about such difficult and complex issues, especially when you consider that –

- trans activists ignore and often oppose the “factuality” of science, which serious non-theists ordinarily value; and

- in an Islamic theocracy, non-theists would fare as badly as feminists and LGBTIQ folk.

As far as I can tell, all these groups have in common is a, shall we say, “warm dislike” of Christianity. I don’t know how else to make sense of this outlandish alliance.

Some non-theists are seriously dedicated to reality and reason and have avoided being ensnared by these movements. It is possible to have positive ethical and political conversations with these more independent non-theists. There is likely to be mutual acceptance of the starting proposition that human beings are highly, and equally, valuable – if the non-theists don’t deride our “deluded” reasons for believing this and we don’t berate them for having no reason at all to believe it (see Part 2). From that starting-point, a lot of positive discussion and common action are possible.

Some very good books

Before closing, I must bring to your attention four excellent myth-busting books that together respond to most charges laid at the door of Christianity:

Karen Armstrong, Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence (2014)

– a history of religion and war – wars, past and present, are usually complex

In these times of rising geopolitical chaos, the need for mutual understanding between cultures has never been more urgent. Religious differences are seen as fuel for violence and warfare. In these pages, one of our greatest writers on religion, Karen Armstrong, amasses a sweeping history of humankind to explore the perceived connection between war and the world’s great creeds—and to issue a passionate defense of the peaceful nature of faith.

With unprecedented scope, Armstrong looks at the whole history of each tradition—not only Christianity and Islam, but also Buddhism, Hinduism, Confucianism, Daoism, and Judaism. Religions, in their earliest days, endowed every aspect of life with meaning, and warfare became bound up with observances of the sacred. Modernity has ushered in an epoch of spectacular violence, although, as Armstrong shows, little of it can be ascribed directly to religion. Nevertheless, she shows us how and in what measure religions came to absorb modern belligerence—and what hope there might be for peace among believers of different faiths in our time.

Paul Copan, Is God a Moral Monster? Making Sense of the Old Testament God (2011)

– a very insightful look at the Old Testament generally, but especially those passages that our critics like to highlight

A recent string of popular-level books written by the New Atheists have leveled the accusation that the God of the Old Testament is nothing but a bully, a murderer, and a cosmic child abuser. This viewpoint is even making inroads into the church. How are Christians to respond to such accusations? And how are we to reconcile the seemingly disconnected natures of God portrayed in the two testaments?

In this timely and readable book, apologist Paul Copan takes on some of the most vexing accusations of our time, including:

God is arrogant and jealous

God punishes people too harshly

God is guilty of ethnic cleansing

God oppresses women

God endorses slavery

Christianity causes violence

and more

Copan not only answers God’s critics, he also shows how to read both the Old and New Testaments faithfully, seeing an unchanging, righteous, and loving God in both.

Bart D. Ehrman, The Triumph of Christianity: How a Forbidden Religion Swept the World (2018)

– Christianity did not spread only because it was adopted by the Emperor Constantine

The “marvelous” (Reza Aslan, bestselling author of Zealot), New York Times bestselling story of how Christianity became the dominant religion in the West.

How did a religion whose first believers were twenty or so illiterate day laborers in a remote part of the empire became the official religion of Rome, converting some thirty million people in just four centuries? In The Triumph of Christianity, early Christian historian Bart D. Ehrman weaves the rigorously-researched answer to this question “into a vivid, nuanced, and enormously readable narrative” (Elaine Pagels, National Book Award-winning author of The Gnostic Gospels), showing how a handful of charismatic characters used a brilliant social strategy and an irresistible message to win over hearts and minds one at a time.

This “humane, thoughtful and intelligent” book (The New York Times Book Review) upends the way we think about the single most important cultural transformation our world has ever seen—one that revolutionized art, music, literature, philosophy, ethics, economics, and law.

David Bentley Hart, Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies (2009)

– covers several bases, including Christianity and science, the Spanish Inquisition, witches and slavery.

Among all the great transitions that have marked Western history, only one—the triumph of Christianity—can be called in the fullest sense a “revolution”

In this provocative book one of the most brilliant scholars of religion today dismantles distorted religious “histories” offered up by Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, and other contemporary critics of religion and advocates of atheism. David Bentley Hart provides a bold correction of the New Atheists’s misrepresentations of the Christian past, countering their polemics with a brilliant account of Christianity and its message of human charity as the most revolutionary movement in all of Western history.

Hart outlines how Christianity transformed the ancient world in ways we may have forgotten: bringing liberation from fatalism, conferring great dignity on human beings, subverting the cruelest aspects of pagan society, and elevating charity above all virtues. He then argues that what we term the “Age of Reason” was in fact the beginning of the eclipse of reason’s authority as a cultural value. Hart closes the book in the present, delineating the ominous consequences of the decline of Christendom in a culture that is built upon its moral and spiritual values.

0 Comments