Foreward

From the printed booklet version of this document

In June 2013 at a hui on bicultural peace-making organised by Laidlaw College, Alistair Reese (Te Kohinga Reconciliation Network) raised the idea of a special statement to mark the Gospel bicentenary.

In July I invited Alistair and David Moko (Baptist Māori Ministries) to lunch to discuss the suggestion and we agreed that a statement should be written, with the caveat from David that if it was to be something that just sat on people’s shelves gathering dust, he was not interested. We all agreed.

In September I shared the initiative at the National Church Leaders Aotearoa New Zealand meeting in Wellington. There was general support, and even a suggestion that the NCLANZ group might organise the writing.

In November, with the bicentenary only weeks away, and a desire that the statement would be available for the NZ Christian Network 2014 Christian Leaders Congress to be held in Waitangi in February, we asked Samuel Carpenter from Karuwhā Trust to prepare an initial draft. Samuel had impeccable credentials being a qualified lawyer, with a master’s degree in history, who had made a submission to the Waitangi Tribunal, and was working at the Office of Treaty Settlements.

The four of us worked on the draft through January with feedback from a number of Māori and Pakeha historians and Christian leaders; Alistair organised translation into Maori; and the statement was presented and well received, in both languages at the Congress.

Feedback was invited from February to July. David Moko and I both travelled extensively during this period talking about the statement on marae and in church ministers’ groups throughout the country.

In August we met via skype, prayed through the responses, and completed the statement for people to sign. It is the prayer of the authors that this would not be seen now as a final word, but rather a catalyst for ongoing dialogue and action.

Thanks to all of my co-authors – Samuel, David, and Alistair. Thanks to Gayann Phillips for the beautiful design work in this booklet. Thanks to all who helped with research and feedback.

To God be all the glory.

Glyn Carpenter, New Zealand Christian Network

November 2014

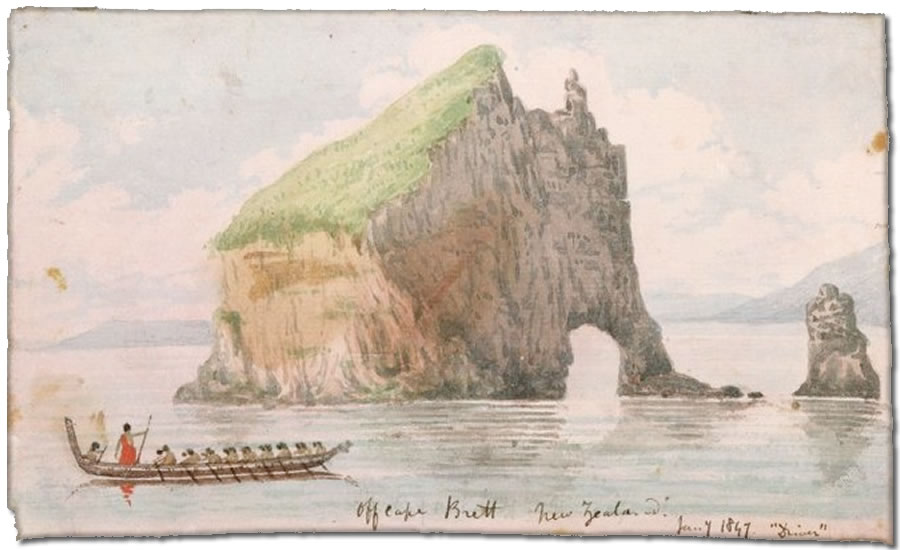

Gold, Charles Emilius (Lieutenant-Colonel), 1809-1871: Off Cape Brett New Zealand. Jany 1847 “Driver” Ref: B-103-019. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22896302

August 2014

This is a discussion paper written to mark the bicentenary of the first recorded preaching of the gospel and the beginnings of Christian mission work in Aotearoa New Zealand.

It is a living statement, a perspective from a vantage point of two centuries of complex history, a contribution to the ongoing conversation on the relationship between ngā iwi Māori and Christian faith and life in its varying expressions.

It is offered in the hope that it will encourage a process of meaningful discussion and kōrero about our shared past and present and the shape of our shared future.

Historical narrative summary

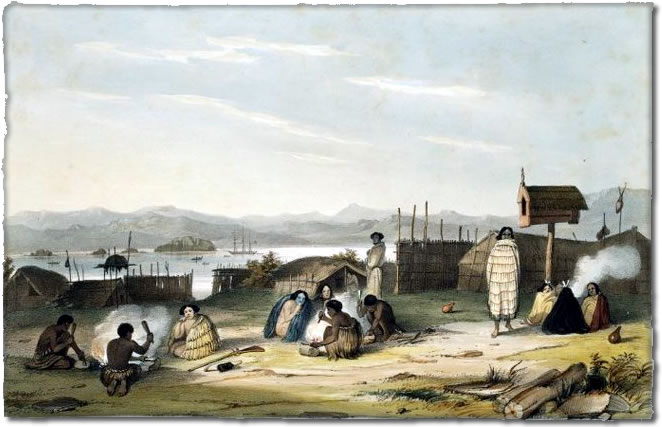

The Polynesian ancestors of the Māori brought with them to Aotearoa beliefs and understandings about the world and its divine origins. Māori saw the world as a unified whole and made little distinction between ‘physical’ and ‘spiritual’ dimensions of life. Spiritual beings animated nature and their blessing was sought before beginning important tasks such as planting crops, fishing, going to war, and starting life in a new land. The world had its origins in the gods, or God, and there is evidence of a ‘supreme being’ in Māori cosmology, in some traditions known as ‘Io’. Io had many names including ‘Io-Matua-Kore’ (Io the Parentless), Io-Mata-Ngaro (Io the Hidden-Face), and Io-nui (Io the great-God).

Māori society emphasized the group or community. Although individuals held land use rights, the land was ‘owned’ by the hapū or group. Only the group could decide to gift or exchange land with outside groups. The social structure was not hierarchical, although tribal leadership was important and in some areas of New Zealand iwi or hapū had ‘paramount’ leaders similar to some parts of Polynesia.

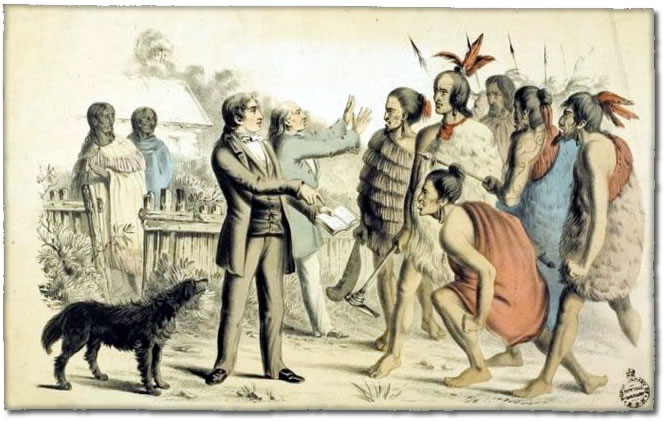

Earle, Augustus 1793-1838 :Sketches illustrative of the Native Inhabitants and Islands of New Zealand from original drawings by Augustus Earle Esq, Draughtsman of H. M. S. “Beagle”. London, Lithographed and Published under the auspices of the New Zealand Association by Robert Martin & Co, 1838. Ref: PUBL-0015-03. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22902207

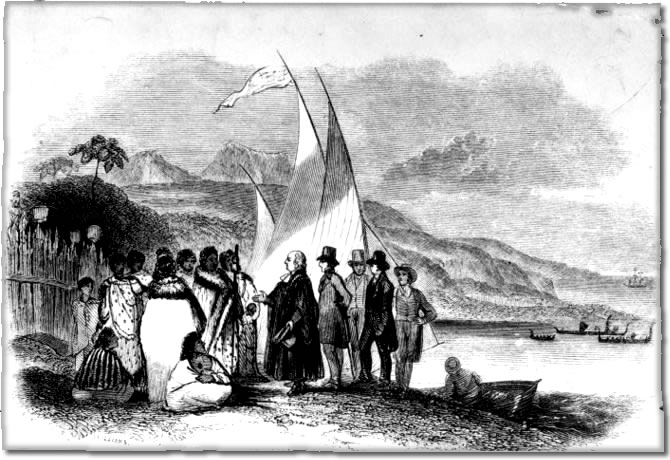

Williams, Samuel, 1788-1853 : Landing of the Rev. S. Marsden in New Zealand, Dec. 19, 1814 [London, 1847]. Annals of the diocese of New Zealand, edited by Sir Charles Jasper. London, Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, 1847. Ref: PUBL-0191-frontis. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23237252

This was the setting of beliefs and social values into which the gospel (the ‘good news’ or ‘te rongopai’) of Jesus Christ came. The gospel was introduced into New Zealand by European missionaries with their own cultural outlook and values. In Aoteaora, the gospel was often accepted within Māori cultural settings, sometimes it was embraced almost completely as he huarahi hou (‘a new way’), and in times of political challenge and turmoil it was a source of inspiration alongside older belief structures. This is the basic pattern of the story to be told briefly below.

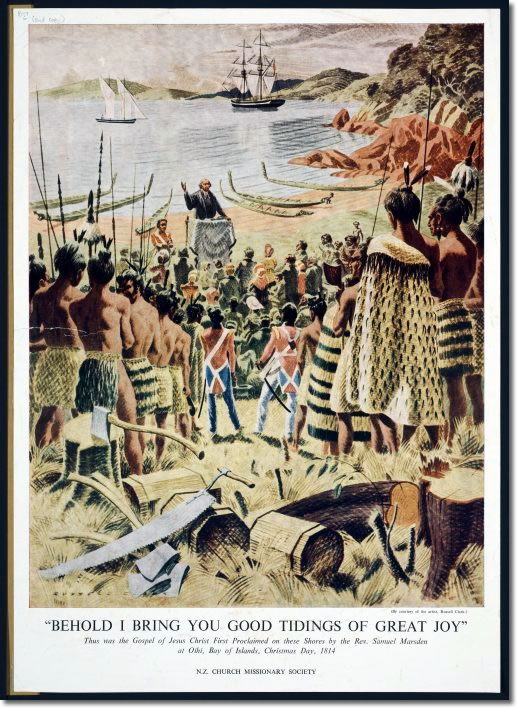

Christian mission work in Aotearoa New Zealand began with real promise, through the relationships established between the Rev. Samuel Marsden of the Anglican Church Missionary Society (CMS) and Māori chiefs visiting New South Wales.

A senior Bay of Islands chief, Te Pahi, was an important early contact for Marsden, and prompted him to consider establishing a CMS mission under Te Pahi’s protection. However Te Pahi died, and his leadership role was assumed by the younger chief Ruatara who had also spent time with Marsden in New South Wales. At Ruatara’s invitation Marsden established the first Christian settlement and conducted the first formal Christian service in New Zealand, near Rangihoua pā in the Bay of Islands, on 25 December 1814. Māori responded to this Christian ceremony with a haka of some 300-400 warriors.

Clark, Russell Stuart 1905-1966: Samuel Marsden’s first service in New Zealand. [Christchurch] N.Z. Church Missionary Society [1964]. Ref: B-077-006. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23220567

Artist unknown: The power of God’s Word. [1856].. [Josenhans, J]: Illustrations of missionary scenes; an offering to youth. Mayence [Mainz], Joseph Scholz publisher, [1856]. 2 volumes. Ref: PUBL-0151-2-013. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23026181

This initial gospel endeavour was soon followed by the arrival of other Christian mission leaders including the CMS Anglican Henry Williams (1823), the Wesleyan Samuel Leigh (1822) and the Roman Catholic Bishop Jean Baptiste François Pompallier (1838). The early mission stations were almost always established under the protection of a local rangatira or chief. Peacemaking endeavours by these missionaries during the ‘musket wars’ and their Māori allies achieved success over time. Peace was often conducted in accordance with Māori custom, with Pākehā missionaries involved. On other occasions, Māori converts themselves acted alone as peacemakers (as in the case of Taumata-a-Kura of Ngāti Porou and the peacemaking with Bay of Plenty iwi in the late 1830s).

Release of many slaves taken captive by northern iwi sparked an indigenous mission movement as those people returned to their home communities with their new found Christian beliefs. Peacemaking, translation of scripture, and the spread of the Christian message, led to a significant transformation of Māori society. Māori were attracted to Christianity in part because its message of peace provided an escape route from cycles of war that had engulfed much of the country in the 1820s and 30s musket wars.

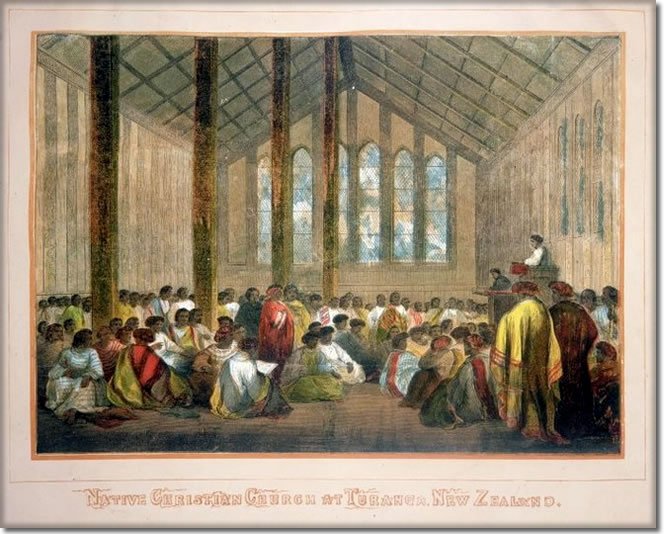

Artist unknown: Native Christian church at Turanga, New Zealand. [1852]. Ref: B-051-017. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zeland. httb://natlib.govt.nz/records/22751176

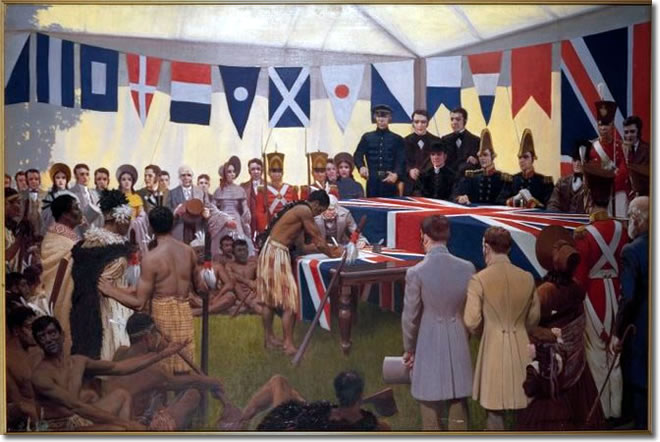

King, Marcus, 1891-1983 :[The signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, February 6th, 1840]. 1938. Ref: G-821-2. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22308135

Although conversions were initially few in number, by the mid-1840s, well over half the Māori population was estimated to be gathering regularly for Christian worship, influenced by Anglican, Wesleyan and Catholic traditions. The work of these European missions was taken up and expanded upon by local practitioners such as Piripi Taumata-a-Kura of Ngāti Porou, Nopera Panakareao of Te Rarawa, Minirapa Rangihatuake of Ngāti Mahanga, Wiremu Tamehana of Ngāti Hauā, Hakaraia Mahika of Waitaha/Tapuika, and Tamehana te Rauparaha of Ngāti Toa, to name a few. These evangelists and teachers witnessed the spread of the gospel from Kaitaia to Rakiura/Stewart Island.

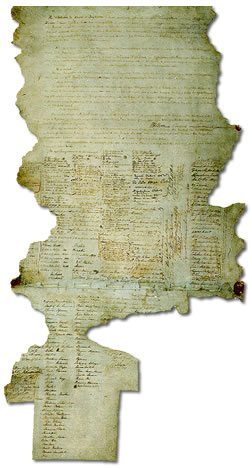

Following requests by iwi leaders for British intervention in a changing and challenging geopolitical milieu, Protestant missionaries brokered the 1840 te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi. They supported the document believing it was the best chance of protecting Māori interests in the face of increasing British settlement. Missionaries carried and explained many of the nine treaty sheets that were signed by Māori throughout the country. In areas where Christian mission teaching had taken root, especially in Northland, some Māori understood the Treaty as akin to a biblical covenant.

Because the involvement by Christians was integral to the Treaty signings, subsequent departures from its terms tarnished the reputation of the missionary churches, even though they were not in most cases responsible for these breaches.

The arrival of settlers after 1840 resulted in increasing conflict over the acquisition of Māori land. The emerging settler churches were preoccupied with their own life. Prominent Christians such as Bishop Selwyn and William Martin were among those who attempted to prevent the adverse effects of colonization for Māori iwi and hapū. The early Native Protectorate, staffed mostly by former missionaries, had a positive influence, but was abolished by the late 1840s.

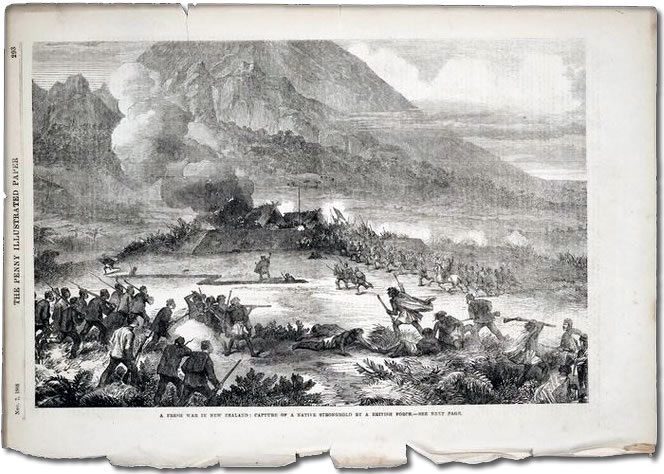

Leading Christians including missionary Octavius Hadfield spoke out against the government’s land dealings in Waitara, Taranaki. A few years later, however, a Christian critique of the 1860s wars and confiscations was lacking. Some Māori perceived Pākehā church leaders as supporting Crown military forces, even though many did not intend to take sides in the conflict. In some instances, church leaders supported the Crown’s prosecution of the war against the Kingitanga and other Māori.

The 1860s wars ruptured many North Island Māori communities, including those where many had become followers of the Christian way. Many Māori left the established churches, some feeling betrayed by a government that now had waged war against them, despite it purporting to be the government of Christian society (as the missionaries had taught them to expect). Prophetic and millennial movements arose inspired by both Māori and biblical ideas. New churches such as Ringatū and, later, Rātana, nourished and sustained Māori communities in troubled times. The traditional Christian denominations did not in most cases meaningfully engage with or support these movements, often seeing them as a threat to orthodoxy. However exceptions did exist, for example the support Methodists, through A J Seamer, gave to Rātana and the Presbyterians, through J G Laughton to Rua Kenana at Maungapōhatu.

Artist unknown: A fresh war in New Zealand; capture of a native stronghold by a British force – “Penny illustrated paper”, 7 November 1868 – 6 February 1869]. Ref: A-423-002. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22815056

Pihopa Herewini – George Augustus Selwyn, D. D., Lord Bishop of New Zealand. Engraved by Samuel Cousins; painted by George Richmond. [London?] Rev. Edward Coleridge, 1842. Ref: G-588. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23006813

Wiremu Matene – William Martin Carpenter. Drawn on stone by J. Dickson from a portrait by J Carpenter. London, 1842.. Ref: C-022-009. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23154861

Octavius Hadfield – Ref: 1/4-002166-G Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23182136

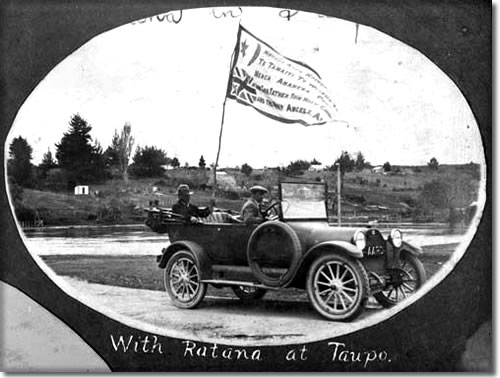

Tahupōtiki Wiremu Rātana, founder of the Rātana Church, carries word of his faith to the Taupō district in the 1920s.

The flag he is holding carries the star and crescent moon symbols of the Rātana Church along with a Union Jack, and the words ‘The Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost’ in both Māori and English.

Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana publicising the Ratana Movement in Taupo. Montgomery, A M: Photograph album of Aard Motor Services Tours. Ref: 1/2-089569-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23254155

A church voice was generally lacking when the Kīngitanga and Kotahitanga movements protested against land loss and confiscation. It was also absent when Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi and their followers resisted government encroachment on their land and community at Parihaka, Taranaki in the late 1870s and early 1880s. They were arrested and imprisoned in Dunedin, many without trial.

Māori communal society was overwhelmed by the introduced Western legal system. Individualization of land tenure in particular, splintered Māori tribal society and undermined its leadership structures. Individualization of title was usually understood as introducing modern benefits to Māori society, but church leaders often failed to perceive or speak out against its harmful effects. Some shining examples of Christian mission and educational endeavour, for example Te Aute College and support for the Young Māori Party, were lights in a rather bleak landscape for many Māori communities and individuals in the mid-to-late nineteenth century and into the twentieth century.

Bridge, Cyprian, 1807-1885: Waimate Mission Station in 1845. [Engraved by] J. Whymper, from a sketch by Col. Bridge. [London, 1859]. Thomson, Arthur Saunders, 1817?-1860: The story of New Zealand (London, John Murray, 1859). Ref: PUBL-0144-1-330. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23165305

Particular instances occurred of churches failing to fulfill earlier promises to build schools on land gifted by local Māori for the education of their children. Technicalities of British law in some cases, church inertia and lack of funds in others, meant the land was not used for that purpose or returned to the original Māori owners. In recent times there are examples of this land being returned to Māori communities.

Christian mission in Aotearoa New Zealand has been hindered at various junctures, but the message of the gospel, heralded by Marsden in 1814, has continued to be received in its various forms by many within the Māori world from the nineteenth century up until the present day.

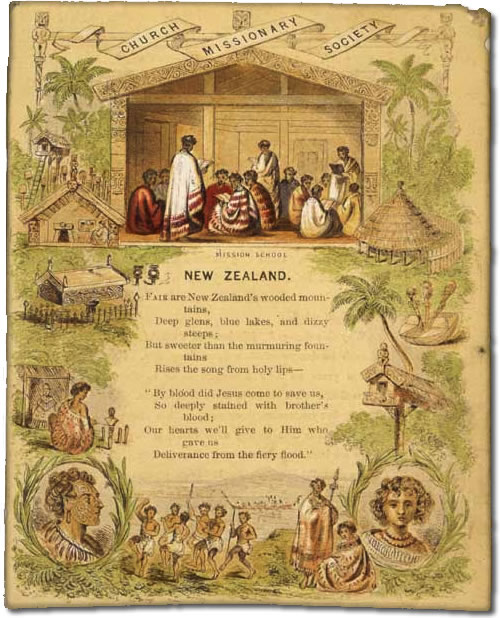

Artist unknown: New Zealand. Mission school. Fair are New Zealand’s wooded mountains … [London?]; Church Missionary Society [1849 or later?]. Ref: A-015-009. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22788222

Acknowledgements and Affirmations

As those who seek to follow Ihu Karaiti/Jesus Christ in this land of Aotearoa New Zealand, we acknowledge the above historical narrative summary and make the following further statements:

1

With the apostle Paul, we declare that we are not ashamed of the gospel, for it is the power of God for the salvation of all who believe (Rom 1:16). We also affirm that God our Creator has made from one blood every nation of men to dwell on the face of the earth and has determined their preappointed times and the boundaries of their habitation, so that they may seek the Lord and find Him…(Acts 17:26-27);

2

We express thankfulness to God and to those Māori and Pākehā Christians who spread the gospel or good news of Ihu Karaiti/ Jesus Christ throughout this land, who sought to follow faithfully the Christian way as individuals and communities, who established many churches, schools and social service agencies, and whose self-sacrificial work sustained many communities in these islands;

3

We acknowledge and affirm Te Reo Māori (Māori language) as an official language in Aotearoa NZ. We remember the establishment of mission schools in te reo Māori, and the study and documentation of te reo, which in time resulted in an outstanding dictionary and many resources in the language, including scripture, liturgy, and educational resources. We affirm te reo Māori as a taonga (treasure) and will endeavour to support the use of the language in Christian services and in new translations of scripture and resources for churches, communities, schools, and the generations that follow;

4

We acknowledge the important role played by Christian missionaries in the drafting and signing of te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi. We affirm the covenant nature of the Treaty, that the Treaty laid a foundation for true partnership between Māori and the Crown, Māori and Pākehā, and all peoples of this land. We affirm our commitment to the Treaty’s key provisions: protecting Māori lands, resources, taonga/treasures and rangatiratanga/chieftainship; providing a foundation for civil government; and conferring equal citizenship on Māori and Pākehā and all peoples who followed them. We also acknowledge the difficulties presented by te Tiriti/the Treaty being in two different languages, which each reflect varying cultural norms and expectations. We affirm, however, that it has been the failure to uphold the spirit and texts of the Treaty –whether Māori or English text –that has been the main ‘Treaty failure’ in New Zealand society.

Tiriti o Waitangi -Treaty of Waitangi Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga Reference: IA 9/9

5

We acknowledge and grieve that the Christian churches have not always honoured the Treaty, and we affirm apologies that have been proffered over recent decades by various individuals, gatherings, denominations, and the Crown. These steps towards reconciliation have recognised that the churches have failed in many instances to honour Māori as tangata whenua and have often failed to stand by them in troubled times. We also acknowledge that the need for reconciliation and restitution is ongoing and often location/denomination specific. We affirm, therefore, the need for churches, mission agencies, individuals, and the Crown, to continue to pursue the ministry of reconciliation and restitution within their own contexts and spheres of influence.

Bishop Kito and Keith Newman sign the Gospel Bicentenary Statement with Glyn Carpenter, David Moko and Mark Grace

Conclusions

The early missionaries believed in a God who would ultimately work out all things according to his own sovereign plan. In the same way we believe that, in spite of human failings and limitations, the Creator’s purposes will be established in these islands. We believe too, in the rule and reign of the Kingdom of God, which like a small kauri sapling grows to become a tree giving life to many things.

Like many who have gone before, we seek to fashion ways of life and faith that are both faithful to Christian scripture and tradition and, at the same time, authentically indigenous to this land of Aotearoa New Zealand.

In line with scriptural principles and the promise of a new world where justice reigns, we affirm our commitment to the proclamation of the gospel and to work for a renewed society in which the great potential of human life within these islands will be fully realized.

And now these three remain: faith, hope and love.

But the greatest of these is love.

1 Corinthians 13:13

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has chosen me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind; to set free the oppressed and announce that the time has come when the Lord will save his people.

Luke 4:18-19

Do you support this statement?

If so, we invite you to indicate your support by signing the form below

Please share this document with your friends, whanau, and colleagues as a first step towards recognising the unique history we share in this land, Aotearoa New Zealand

Click here to add your digital signature

[gravityform id=”8″]