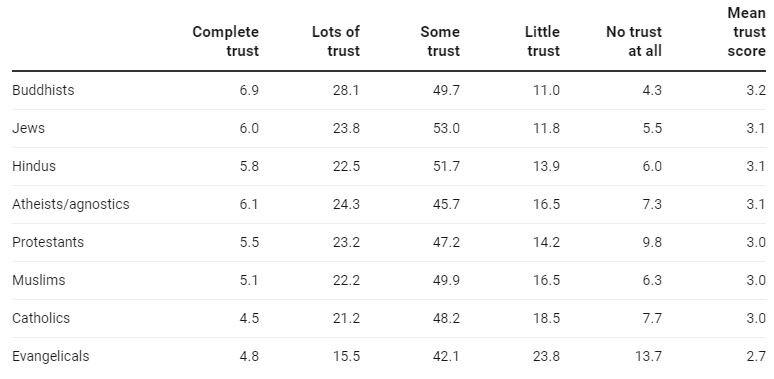

A number of media have recently carried a story about a survey seeking to measure which religions in New Zealand are the most-trusted, and which are the least trusted, in the aftermath of the 15 March terrorist attacks in Christchurch. The survey, conducted by the Institute for Governance and Policy Studies at Victoria University of Wellington, was based on a sample of one thousand people. Respondents were asked to indicate their trust in the following “religions”: Catholics, Protestants, Evangelical Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, atheists or agnostics, and Jews.

The summary that was headlined was “BUDDHISTS MOST TRUSTED, EVANGELICALS LEAST”. Respondents to the survey awarded Buddhists the most trust (35%) and the least distrust (15%). “Evangelical Christians” attracted the least trust (21%) and the most distrust (38%). All other “religions” were in a statistically indistinguishable clump in the middle.

The summary that was headlined was “BUDDHISTS MOST TRUSTED, EVANGELICALS LEAST”. Respondents to the survey awarded Buddhists the most trust (35%) and the least distrust (15%). “Evangelical Christians” attracted the least trust (21%) and the most distrust (38%). All other “religions” were in a statistically indistinguishable clump in the middle.

It is not surprising that Buddhists, with their reputation for peacefulness and for harmony with nature, were the most trusted religion in a society where many secular people (now over 40% of New Zealanders) are at least faintly drawn to the sort of diffused spirituality perceived to be associated with eastern religion. Also, Buddhists do not have a reputation for being out to convert anyone.

Given the way the survey was framed, it was perhaps inevitable that respondents would indicate the lowest degree of trust in “evangelicals”.

A number of comments can be made about the survey…

1

Most people in New Zealand – especially secular people, but also probably the majority of church-going Christians –have little or no idea what the term “evangelical” means (i.e. that it is a theological category, denoting a strong emphasis on the Gospel and the Bible).

2

The majority of people who are evangelical in New Zealand (and in most other countries), do not usually explicitly identify themselves as “evangelical”, but more often primarily identify themselves as “Christian” or by the name of their church or denomination, or by some other theological descriptor such as “Pentecostal”. Many New Zealand “Evangelicals” are in so-called mainstream churches, and many others in denominations such as the Baptists, or in independent churches. It is erroneous to assume that because only a mere 15,000 people explicitly identified themselves in the 2013 Census as “Evangelical”, they are the only people in New Zealand who are evangelical.

3

It was odd and confusing that the survey singled out “Evangelical” as one of the options, and “Protestant” as another. “Evangelical” and “Protestant” are not in fact separate or competing “religions”. The reality is, the majority of “Evangelical” Christians are also “Protestant”, and about half of New Zealand’s church-going Protestants are also evangelical in theology and practice. One term is essentially a subset of the other. So comparing one with the other is rather like comparing apples with fruit.

4

For many respondents, the word “evangelical” was probably misunderstood to mean “evangelistic”. For many people the word conjures up feelings about in-your-face, bible-bashing proselytism, something which many secular people find annoying (and which many Christian people are also uncomfortable with).

5

It is also highly likely that quite a number of respondents were also influenced by the American media’s highlighting of “evangelical” support for the Republican Party and especially for Donald Trump. The word “Evangelical” thus invokes some negative stereotypes, and for the survey to single out “evangelicals” at this time was almost to invite such a response. In our greatly different New Zealand context, however, it is fallacious to suppose that all New Zealand “Evangelicals” must be Trump-supporting, Muslim-hating bigots and xenophobes. Notwithstanding the current linkage in the United States between some evangelicals and political views, in almost every other country in the world the word “evangelical” carries no political meaning at all.

For all these reasons, it is questionable whether the survey offers us any useful new insights. Indirectly, however, the outcomes of the survey are consistent with what many of us already knew: that the term “evangelical” is currently not well known or understood within wider New Zealand society, nor even within many New Zealand churches.

But, as indicated in another article posted today (see here), the true taonga in the word “evangelical” lies not in the word itself but in what it points to, the Good News of Jesus.

0 Comments