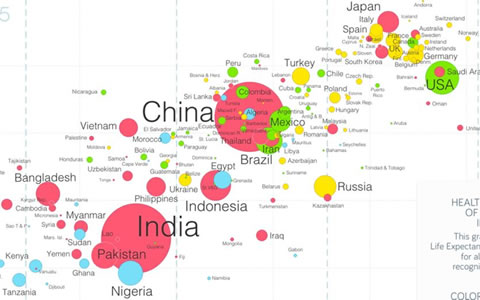

“Is the world getting better, worse or staying the same?”

If you think it is getting worse, you’re in good company. The majority of audiences in 30 countries who were asked this question believed that things were indeed getting worse in our world. Among Christians too, many are predisposed to a negative perspective as wars, famines, persecutions and earthquakes have always been stuff of end-time scenarios.

But is this true? Or do most of us have a distorted worldview? Until his death two years ago, Swedish health professor Hans Rosling battled deeply-rooted misconceptions held by top academics, economists, UN officials, politicians, military brass and journalists concerning the state of the world, in boardrooms, lecture halls, and forums from Davos to TED talks.

A medical doctor with vast hands-on experience in many countries, Rosling challenged his listeners to seek out the facts and develop a lifestyle of what he called ‘Factfulness’, the title of the book he completed in the last months of his life.

Yesterday in the first Boekhoek (bookcorner) of this year in the Upper Room salon in Amsterdam, we examined some of the facts Rosling would present to his audiences about bad things decreasing, like the following:

• extreme global poverty has fallen from 85% in 1800 to 9% in 2017, the biggest drop from 50% happening since 1966.

• average life expectancy has risen from 31 years in 1800 to 72 years in 2017.

• today there are no countries with a life expectancy below 50 years.

• in 1800, 44% of children died before the age of 5 years, but in 2016 only 4% died.

• battle deaths per 100,000 people was 201 in 1942, but today is merely 1.

• plane crash deaths per 10 billion passenger miles over 5-year averages was 2100 in 1929-1933, but 2012-16 was 1.

• deaths from disasters annually over 10-year averages per million people was 453 in the 1930s, reduced to 10 over the period 2010-16.

• child labour of those 5-14 years working full-time under bad conditions dropped from 28% in 1950 to 10% in 2012.

• nuclear arms reached a peak of 64,000 warheads in 1986 but was reduced to 15,000 in 2017.

• 148 countries had cases of smallpox in 1850, yet smallpox was eradicated by 1979.

• world hunger has dropped from 28% of people undernourished in 1970 to 11% in 2015.

Facts about good things increasing that Rosling would tell his audiences included:

• cereal harvests (tonnes per hectare) have increased from 1.4 in 1961 to 4 in 2014.

• adult literacy has increased from 10% in 1800 to 86% in 2016.

• the share of humanity living in a democracy has risen from 1% in 1816 to 56% in 2015.

• the countries with equal voting rights from women and men was 1 in 1893, but today is 193.

• child cancer survival has risen from 58% in 1975 to 80% in 2010.

• the share of girls enrolled in primary schools was 65% in 1970 and in 2015 was 90%.

• one-year-olds vaccinated at least once have risen from 22% in 1980 to 88% in 2016.

• those with access to water from a protected source is 85% in 2015, up from 58% in 1980.

Our problem, Rosling pinpointed, was our tendency to notice the bad more than the good, our ‘negativity instinct’. We tended to romanticise the past into the ‘good old days’. Lack of memory in our ‘now’ culture robbed us of proper reference points. Our news media bombarded us with negative news from all across the world, he wrote: ‘wars, famines, natural disasters, political mistakes, corruption, budget cuts, diseases, mass layoffs, acts of terror’. Our surveillance of suffering had improved tremendously, yet stories about gradual improvements impacting millions of lives didn’t make the front pages. Activists and lobbyists made it their business to create alarm, and thus raise funding, for their causes.

Politicians, journalists and terrorists also exploit the ‘fear instinct’. While terrorism has increased worldwide, it has decreased in the richer nations (less than 1500 were killed from 2007-2016, a third of the number killed in the previous decade); most of the increase has been in Iraq (about half), Afghanistan, Nigeria, Pakistan and Syria. The ‘blame instinct’ is another factor giving us a distorted worldview, said Rosling, the instinct to find a simple reason why something bad has happened, when in fact the causes are usually more complicated.

Rosling was a man of deep humanitarian and humanist compassion. As far as I know, he did not write as a Christian. Yet, despite criticism of its ‘one-sidedness’, Factfulness challenges our world perceptions deeply. His passion for those still trapped in poverty and sickness is evident in his many Youtube videos. He unmasks many of the populist arguments which create fear of foreigners and scapegoat outsiders, and which too many Christians find attractive.

As we have written earlier, the progress he describes is indebted to values spread globally by the missionary movement. Surely there is some overlap between the advance of human wellbeing and flourishing he maps and the biblical concept of ‘shalom’, within the framework of God’s common grace, creating conditions for the gospel to be spread.

And that’s worth a prayer of thanks.

0 Comments