by Gavan O'Farrell | 28 Aug , 2019 | Articles, Christianity in New Zealand, FOCUS, Secularism

“Who are these atheists, anyway?” is the fourth and final part in the Atheism is not all it’s cracked up to be series by Gavan O’ Farrell, who works as a public sector lawyer.

Part one can be read here: Reason and Evidence

Part two can be read here: Morality and the Human Being

Part three can be read here: I don’t want it, so it isn’t there!

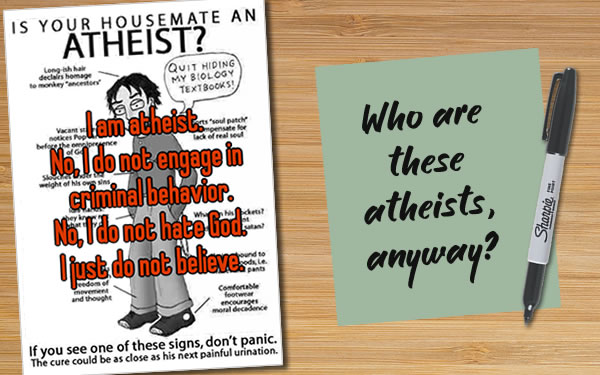

“Who are these atheists, anyway?”

This final Part on the series on atheism is less concerned with argument and more focused on who we’re talking about (and to).

“Non-theists” vary

I’ve decided now to refer to “non-theists”, as non-belief in God ranges from frank atheism (“There is no God”) to agnosticism (“I don’t know”) with each position having its own spectrum and labels not being applied consistently. Non-theists sometimes describe themselves as “rationalists”, “realists”, “sceptics”, “humanists” or “secularists”. However, they all reside in the “empiricist box” (see Part 1).

I’ve decided now to refer to “non-theists”, as non-belief in God ranges from frank atheism (“There is no God”) to agnosticism (“I don’t know”) with each position having its own spectrum and labels not being applied consistently. Non-theists sometimes describe themselves as “rationalists”, “realists”, “sceptics”, “humanists” or “secularists”. However, they all reside in the “empiricist box” (see Part 1).

Needless to say, non-theists vary because they are human beings with myriad characteristics and experiences. I can mention some.

The most serious non-theists are those atheists who are intellectually attached to the evidence argument: if there were a God, it would have been proved by now. Their demeanour varies: some triumphalist and rude, some civil.

Ordinarily, atheists are a smallish subset of non-theists but, in this era of maximum self-expression, the number is probably artificially inflated.

The most visible non-theists are those who have a strong dislike of religion, especially Christianity.

This dislike may arise from their understanding of the general and historical conduct of the Church – sometimes a genuine misunderstanding that can be treated with information.

Illumination is not effective when the misunderstanding is deliberate – due to prejudice or even organised enmity. Socialists, for example, oppose Christianity as a matter of ideology, will contradict and abuse it at every opportunity and intend to bring it down. This stance can be found in many places, people and discussions: it doesn’t always call itself Socialism but, on the other hand, the Socialism brand is being laundered and relaunched despite its appallingly murderous history.

Or the dislike may be the result of bad experiences within the Church – a story which needs to be seriously listened to before mentioning “babies and bathwater”. Many are angry: mere indignation for some, while for others it is real hurt.

This anger is sometimes directed at God, not at religion. If a believer is angry with God, and doesn’t address the situation properly, the anger can take them far away – eg I might “punish God” by proclaiming that I don’t believe in Him.

Determined personal sovereignty and autonomy is another path to non-theism: “I don’t need a God to feel significant or secure”. Or, “I’m very clever and educated, I’ll take it from here”. Or simply, “No-one’s the boss of me!” More attitude than rationale.

Others were raised as non-theists and, like some Christians, think habitually and speak by rote.

Some non-theists call themselves “sceptics”, but I have found that they are typically half-sceptics – sceptical about God and the supernatural but not about their own claims about rationality and evidence (or the social and moral positions put forward by the Left).

Most non-theists are agnostics. This position is more understandable than a dogmatic “Ain’t no God”.

On the other hand, “I don’t know” is often a cover for “I don’t care”. It seems strange not to care that there might be Someone who made the cosmos and is in touch with humanity, but we continue to hear “I’ll cross that bridge when I get to it”.

On the other hand, “I don’t know” is often a cover for “I don’t care”. It seems strange not to care that there might be Someone who made the cosmos and is in touch with humanity, but we continue to hear “I’ll cross that bridge when I get to it”.

For some, “I’ll cross that bridge” is another pretext for avoiding a difficult issue. We should recognise that delaying consideration (and the “risk” of believing) is understandable, just like not wanting God to exist.

Some people prefer agnosticism because they believe it can accommodate spirituality. (Oddly, even some atheists are into this.) Of course, this “spirituality” falls short of belief in a God who is a Person – especially, a Person with, shall we say, “strong opinions” (who needs that?!). I think they’re trying to have their cake and eat it:

- A yearning for “the spiritual” is extremely common and entirely natural (a hint at the real yearning for God).

- However, with no connection with God or the supernatural, “spirituality” is just a species of strong emotion.

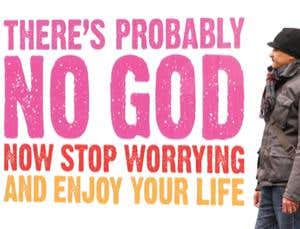

- True atheism – “truth is about reason and evidence” – is hard to market. No-one wants to think of themselves as a left hemisphere on a stick, so no wonder non-theist advocates use hard-sell. Enhancing non-theism with “spirituality” is smart marketing, but that’s all it is.

At risk of stating the obvious, a conversation with a non-theist is not a conversation with the embodiment of some ideas but with a fabulously complex and unique human being who is in God’s image and likeness, is loved by God, is in humanity’s shared predicament and has an irrefutable claim on everyone’s love.

At risk of stating the obvious, a conversation with a non-theist is not a conversation with the embodiment of some ideas but with a fabulously complex and unique human being who is in God’s image and likeness, is loved by God, is in humanity’s shared predicament and has an irrefutable claim on everyone’s love.

Atheism and politics

Visiting an atheist site, I once asked “Are there any conservative atheists or are you all Lefties?”. I was told, “If you’re smart enough to be an atheist, you’re probably smart enough to be progressive”.

Like much of academia, the media, the education system,much of government and parts of the Church, popular non-theism seems to have been infiltrated and largely taken over by “progressives” – to be politically allied with third-wave feminism, the LGBTIQ lobby and other “diversity” lobbies, and united with these in protecting Islam from criticism.

It is strange that such independent thinkers (a claim which non-theists often make to distinguish themselves from Christians) should all of a sudden be of one mind about such difficult and complex issues, especially when you consider that –

- trans activists ignore and often oppose the “factuality” of science, which serious non-theists ordinarily value; and

- in an Islamic theocracy, non-theists would fare as badly as feminists and LGBTIQ folk.

As far as I can tell, all these groups have in common is a, shall we say, “warm dislike” of Christianity. I don’t know how else to make sense of this outlandish alliance.

Some non-theists are seriously dedicated to reality and reason and have avoided being ensnared by these movements. It is possible to have positive ethical and political conversations with these more independent non-theists. There is likely to be mutual acceptance of the starting proposition that human beings are highly, and equally, valuable – if the non-theists don’t deride our “deluded” reasons for believing this and we don’t berate them for having no reason at all to believe it (see Part 2). From that starting-point, a lot of positive discussion and common action are possible.

Some very good books

Before closing, I must bring to your attention four excellent myth-busting books that together respond to most charges laid at the door of Christianity:

Karen Armstrong, Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence (2014)

– a history of religion and war – wars, past and present, are usually complex

In these times of rising geopolitical chaos, the need for mutual understanding between cultures has never been more urgent. Religious differences are seen as fuel for violence and warfare. In these pages, one of our greatest writers on religion, Karen Armstrong, amasses a sweeping history of humankind to explore the perceived connection between war and the world’s great creeds—and to issue a passionate defense of the peaceful nature of faith.

With unprecedented scope, Armstrong looks at the whole history of each tradition—not only Christianity and Islam, but also Buddhism, Hinduism, Confucianism, Daoism, and Judaism. Religions, in their earliest days, endowed every aspect of life with meaning, and warfare became bound up with observances of the sacred. Modernity has ushered in an epoch of spectacular violence, although, as Armstrong shows, little of it can be ascribed directly to religion. Nevertheless, she shows us how and in what measure religions came to absorb modern belligerence—and what hope there might be for peace among believers of different faiths in our time.

Paul Copan, Is God a Moral Monster? Making Sense of the Old Testament God (2011)

– a very insightful look at the Old Testament generally, but especially those passages that our critics like to highlight

A recent string of popular-level books written by the New Atheists have leveled the accusation that the God of the Old Testament is nothing but a bully, a murderer, and a cosmic child abuser. This viewpoint is even making inroads into the church. How are Christians to respond to such accusations? And how are we to reconcile the seemingly disconnected natures of God portrayed in the two testaments?

In this timely and readable book, apologist Paul Copan takes on some of the most vexing accusations of our time, including:

God is arrogant and jealous

God punishes people too harshly

God is guilty of ethnic cleansing

God oppresses women

God endorses slavery

Christianity causes violence

and more

Copan not only answers God’s critics, he also shows how to read both the Old and New Testaments faithfully, seeing an unchanging, righteous, and loving God in both.

Bart D. Ehrman, The Triumph of Christianity: How a Forbidden Religion Swept the World (2018)

– Christianity did not spread only because it was adopted by the Emperor Constantine

The “marvelous” (Reza Aslan, bestselling author of Zealot), New York Times bestselling story of how Christianity became the dominant religion in the West.

How did a religion whose first believers were twenty or so illiterate day laborers in a remote part of the empire became the official religion of Rome, converting some thirty million people in just four centuries? In The Triumph of Christianity, early Christian historian Bart D. Ehrman weaves the rigorously-researched answer to this question “into a vivid, nuanced, and enormously readable narrative” (Elaine Pagels, National Book Award-winning author of The Gnostic Gospels), showing how a handful of charismatic characters used a brilliant social strategy and an irresistible message to win over hearts and minds one at a time.

This “humane, thoughtful and intelligent” book (The New York Times Book Review) upends the way we think about the single most important cultural transformation our world has ever seen—one that revolutionized art, music, literature, philosophy, ethics, economics, and law.

David Bentley Hart, Atheist Delusions: The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies (2009)

– covers several bases, including Christianity and science, the Spanish Inquisition, witches and slavery.

Among all the great transitions that have marked Western history, only one—the triumph of Christianity—can be called in the fullest sense a “revolution”

In this provocative book one of the most brilliant scholars of religion today dismantles distorted religious “histories” offered up by Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, and other contemporary critics of religion and advocates of atheism. David Bentley Hart provides a bold correction of the New Atheists’s misrepresentations of the Christian past, countering their polemics with a brilliant account of Christianity and its message of human charity as the most revolutionary movement in all of Western history.

Hart outlines how Christianity transformed the ancient world in ways we may have forgotten: bringing liberation from fatalism, conferring great dignity on human beings, subverting the cruelest aspects of pagan society, and elevating charity above all virtues. He then argues that what we term the “Age of Reason” was in fact the beginning of the eclipse of reason’s authority as a cultural value. Hart closes the book in the present, delineating the ominous consequences of the decline of Christendom in a culture that is built upon its moral and spiritual values.

by Gavan O'Farrell | 17 Jul , 2019 | Christianity in New Zealand

“I don’t want it, so it isn’t there!” is the third part in the Atheism is not all it’s cracked up to be series by Gavan O’ Farrell, who works as a public sector lawyer.

Part one can be read here: Reason and Evidence

Part two can be read here: Morality and the Human Being

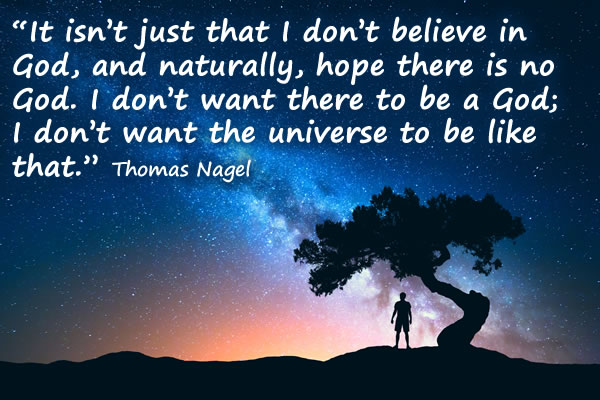

“I don’t want it, so it isn’t there!”

So far, this series on atheism has discussed whether we theists are “irrational” (Part 1) and whether morality is viable without God (Part 2).

I’ll now briefly canvas some of the other things atheists often say.

Two seemingly peripheral arguments

“Which religion?”: A common reason for rejecting God seems to be: “There are thousands of religions, most of them mutually incompatible, they can’t all be true.”

You’d have to look hard to find “thousands”. Anyway, however many there are, my response is “If you are curious, you will do the work of inquiring, just as a serious scientist does when faced with a difficult and complex natural question. If you are not curious, or not willing to do the work, just say so”.

This atheist assertion insinuates, “Religions can’t all be true, so none of them are”, which is clearly illogical: one of them could be true, the atheist just doesn’t know which one. The pervasiveness of theistic belief (globally and throughout history) should really make a genuine sceptic curious.

The “onus of proof”: You will often hear atheists say it is up to theists to prove God’s existence. This made better sense when Christians were doing the talking while the atheists just appraised the arguments.

This has changed, atheists now make a positive assertion “You may not claim a fact unless there is empirical/scientific proof of that fact”. They are now on the front foot, pushing their [limited and limiting] theory of knowledge.

We do wish to persuade about God, but it’s not a matter of “proof” (see Part 1). As I understand the dynamics, we Christians commend our faith to others. I haven’t noticed any Christians insisting on belief in God – not recently, anyway. By contrast, atheists insist that it is only permissible to talk facts (including facts about God) if those facts are proved empirically/scientifically. This insistence swings the onus of proof onto them: they may no longer assume this view and impose it, they must establish it.

It is worth remarking that the location of the onus of proof has no bearing on the issue of whether or not God exists: it’s just a discussion protocol.

I mention these arguments, not because they are intrinsically important but because they come up so frequently. They have negligible logical value as arguments. Really, they seem to me to be excuses rather than arguments – attempted justification for not believing and for not being inquisitive. Another refuge, like the “empiricist box” (Part 1).

It won’t hurt us to acknowledge that not wanting God to exist is entirely understandable. We all value our autonomy and we’re all at least half-inclined to resent authority. Even faith (a shifting, moody thing) is not a 24-7, airtight defence against this.

I wouldn’t be surprised if simply not wanting God to exist turned out to be the central point. And, to the extent that we Christians can empathise, a meeting-point.

“Christianity is not ‘good news’ but bad news”

Atheists often say Christianity is evil and offer a bundle of “proofs” which have become familiar – war, forced conversion, the Spanish Inquisition, witch-hunting, tolerance of slavery, the oppression of women and gays, the suppression of science and, more recently, protected paedophilia. To this list might be added Old Testament violence and the “immoral” nature of Redemption by Christ’s death.

Sometimes, atheists add that they would refuse to worship a God who is behind all of this – a strange assertion that wants to sound heroic but can’t possibly be if there is no God.

Atheists should hesitate before offering moral judgements (see Part 2) but, on the other hand, we Christians should not rely on this to avoid discussion of wrongs we know the Church has done. After all, the Church consists largely of human beings and has wielded enormous power – a notoriously dangerous combination. For the most part, though, the proofs rely on the hasty acceptance of information that is skewed or incomplete.

Christianiy’s track record is critical to the plausibility of Christianity because it is difficult to recommend Christ if history shows that accepting this recommendation is a bad idea. In Part 4, I’ll mention some books that help set our track record straight.

The dark side of this track record is also another excuse for not being inquisitive, this time about Christianity. After all, atheists don’t seem to consider the possibility that God might also be appalled at some things the Church has done.

The attack on Redemption is a separate matter, and is entirely misconceived. Our critics liken it to the ancient ritual of “scapegoating”, where a village would seize a goat, load it up with paraphernalia representing the village’s sins and drive it into the desert so that the sins (and the goat) are never seen again.

We believe Christ volunteered to, so to speak, “carry our sins into the desert”, that He did this long ago without any urging from you or me, that He returned in excellent condition and that He now asks us whether the sins He bore included ours. We say Yes, not to be cruel, but out of common sense and awe-struck gratitude. It would be unspeakably stupid to say No.

by Gavan O'Farrell | 20 Jun , 2019 | Christianity in New Zealand

‘Morality and the human being‘ is the second part in the Atheism is not all it’s cracked up to be series by Gavan O’ Farrell, who works as a public sector lawyer.

‘Morality and the human being‘ is the second part in the Atheism is not all it’s cracked up to be series by Gavan O’ Farrell, who works as a public sector lawyer.

Part one can be read here: Reason and Evidence

MORALITY AND THE HUMAN BEING

Atheists say that Christians often accuse them of being wicked. Such an accusation (which I’ve personally never heard in New Zealand) is not only rude but false: it is quite apparent that many atheists are very moral people.

However, this is despite their atheism. I say this because I suggest that atheists cannot explain their morals. The morals of virtually all atheists are inherited from Christianity – especially the very basic ideas that human beings are highly (and equally) significant.

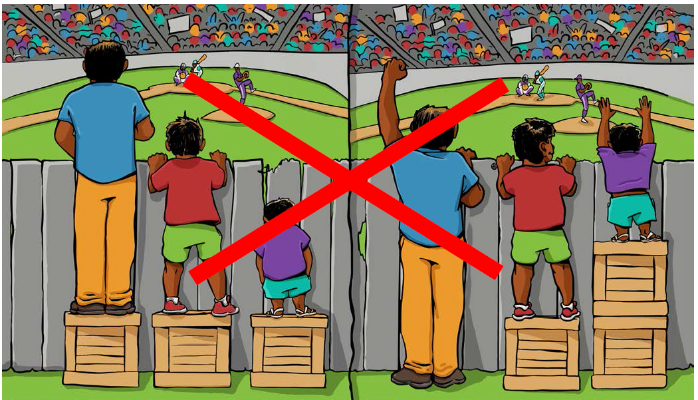

After all, New Zealand’s secularism is post-Christian: it didn’t arrive out of the blue, like a baby delivered by a stork. Like a real baby, it was generated organically and possesses inherited traits.

Moral relativism

Moral relativism

Most atheists say they are moral relativists, who believe there are no “objective” moral requirements that apply to everyone. For them, what we think is an objective morality is just the set of moral constructs developed by our society. Other societies have theirs too and it is impossible to judge another society, no matter what it does, because there is no objective global standard. Many moral relativists go further and say that relativism operates at the individual level: “my morality and my right/wrong” vs “your morality etc”.

As I understand it, moral relativism has long been discredited in philosophical circles. For example, when they promote “tolerance” of other views as being immune from criticism, they insist on this tolerance as an absolute requirement – which contradicts their whole position.

In addition, relativism doesn’t capture the reality of moral discourse. When two people disagree about a moral question, their views are in conflict. However, if two relativists “disagree”, their views don’t conflict because they’re describing their respective moral feelings about the topic, not the moral character of the topic itself (because it has no objective moral character). Their “disagreement” is like A and B discussing headaches, with A saying “I have a headache” and B replying “Well, I don’t have a headache”.

Anyhow, I have found that people who call themselves relativists don’t really seem to mean it. They use it to ward off criticism directed at them: “That’s just your right and wrong (etc)”. But, when they criticise others, they tend to speak very dogmatically, as though there is an objective standard (which they don’t explain).

It is tempting to disdain relativism, but it remains important because a large number of people nominally subscribe to it.

Objective secular morality

Some atheists do acknowledge that morality consists of objective rules, or at least principles, that apply to every individual and every society.

Evolved morality:

Some atheists believe that basic “moral” behaviours (eg altruism) evolved in order for societies (or humanity itself) to survive.

I accept evolution, but it just “happens”, it doesn’t give value and has no authority. We don’t obey moral rules (eg behave altruistically) just because we find them in our midst. We need a reason to obey them.

If we are urged to obey for the sake of the survival of humanity, we can still ask why humanity “should” survive. There is an epic urge to survive, but this is different from “should”. Especially nowadays, when some say we shouldn’t survive because of the harm we’ve caused to the environment.

Deduced morality:

Other atheists try to develop an objective secular morality from the ground up.

Consequentialism:

This approach to morality says an action is right or wrong according to its consequences. However –

- By speaking of good and bad consequences, this approach again assumes certain values (eg survival or well-being) and just imposes them. Besides, whose well-being are we supposed to value, and why? Just humans? All humans?

- Consequentialism rests on the idea that the ends justify the means, and we all know how ruthless and dangerous that can be.

- A consequentialist moral rule is only a rule-of-thumb. If lying is morally wrong because it usually does more harm than good, I must still decide what my specific intended lie will cause.

- I can only consider the foreseeable consequences: the actual consequences are yet to occur. A consequentialist can’t judge an action until afterwards. We need to know beforehand!

- And my decision could take ages. Every action has myriad consequences that go forever. This is unworkable.

- Workable or not, any rules emerging from consequentialism are made by human beings. I end up being completely subject to majority rule. We know the majority can be wrong, which reminds us that the majority has power, not moral authority.

- Consideration of consequences is an important element of moral decision-making, but it’s not all there is to it.

Positivism:

The alternative approach is “positivism”: the rules identify behaviour that is considered to be inherently right or wrong. EG lying is inherently wrong, wrong by its nature, no calculations are needed. This is more realistic and workable as it relies on an intuitive repugnance for lying rather than a remote sense that the lie might do more harm than good.

However, secular positivism also assumes values and also subjects us to the dubious moral authority of the majority.

The human being:

When all the theorising about morality is done, nothing beats a rich definition of the human being as a reason for us behaving well towards each other.

However, relying on “the evidence”, the atheist tells us that human beings are no more than the latest gorilla upgrade, the planet’s most complex organism and top predator and that each of us is a mixed bag of kindness and malice. If this is all a human is, it makes equal sense to hate them as to love them.

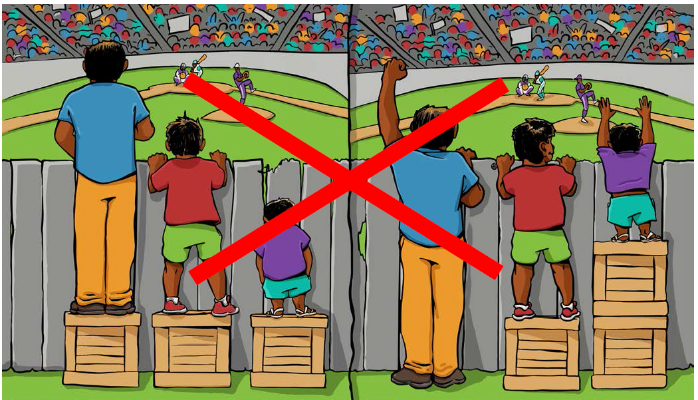

Atheists talk about justice because they believe in equality. Good, but the evidence says people are not equal: many differences are socially constructed, but there are also real inherent superiorities (eg intelligence, strength, agility, prowess, disposition).

We Christians believe each human being to be extremely significant and equally so, regardless of other characteristics, because we are made in God’s image and likeness. This Imago Dei is the trump card. Loving people and giving them justice makes immediate sense because of what they are: a human being demands love and justice simply by being a human being.

Secularists reject all this, of course, and have not yet identified (or even imagined) anything lovable to replace it. The basics of post-Christian secular morality are really a memory of Christianity.

Afterthought

It may be that the atheists’ difficulty in explaining the value of the individual human being has helped give rise to the new ethos, identity politics. While this ethos pays lip-service to “human rights”, it has actually moved well away from the idea of valuing each person individually. Identity politics sees only groups.

Groups are certainly important, but only because they are groups of individual human beings: the value of the group is the result of simple arithmetic.

Identity politics doesn’t get this. After all, it creates the groups – herds, really. Identity politics displays the astonishing arrogance of beholding a spectacularly complex and unique human being and allocating them to a herd by reference to a handful of characteristics (sex, “gender”, sexual orientation, race). So much about each person is simply ignored! Then the herders tell us which herd is “good” and which is “bad”.

Identity politics is spurious, of course, but it must be taken seriously because it has become so powerful (and dangerous). While many atheists are on the political Left, the more serious among them may have to break ranks from identity politics in due course, for the sake of intellectual integrity.

by Gavan O'Farrell | 22 May , 2019 | Christianity in New Zealand

REASON AND EVIDENCE

Every now and then, one reads in the press that “religion is irrational”. In fact, it occurs with increasing frequency – far more often than I would like, speaking as a churchgoer.

Or it might be “belief in God is irrational”, or someone might refer to “faith vs reason” as phenomena in mutual opposition. Or, belief in God might be frankly compared with belief in the Tooth Fairy or Santa Claus or someone even more remote and implausible.

This view of religious belief has been around for some time. What’s changed, besides the frequency of the statement, is the confidence with which it is made. It used to be a claim, now it’s more like a statement of accepted fact, as though it were preceded by “And, of course” or “As we all know”.

Although it’s a popular view in some quarters, it is demonstrably untrue. I’ve noticed that people of faith use reason just as anyone else does. It’s unavoidable: if you don’t apply the rules of logic (to draw reliable conclusions from stated facts and to adopt consistent conclusions), you’ll get called on it every time and attempts at communication would just break down. This doesn’t happen. Whatever we people of faith are, we’re not irrational.

The reason we sometimes reach different conclusions from our critics is not that we don’t use the common logic, it’s because we rely on additional facts (about God) to begin with. I should say “factual assertions” as these facts are contentious.

Speaking from a scientific viewpoint, atheist apologists typically require empirical evidence (evidence which, ultimately, appeals to our senses) to support any factual assertion. This is why we theists might be told, “Come back with some evidence and we’ll talk.”

This is the actual objection to belief in God.

So, in public critique of theism, “reason” and “rationality” are actually a red herring. Some of our critics are aware of this (it’s obvious enough, after all). So, if you were to ask why they call us “irrational”, I can only surmise that it’s because that’s what they “were told”. Tracing it back through atheist whispers, I think you’ll find that the promoters of this view believe “irrational” makes for better polemical marketing than “not evidence-based”. And they’re right. Also, “irrational” is insulting, which is a plus for many of our critics.

Still, the real objection to belief in God – the lack of “evidence” – is serious and important.

For the sake of argument, I accept that the required evidence is not available. I cannot demonstrate how to reliably observe God with the naked eye, with a telescope, microscope or other visual aid, or with any other sense or sense-enhancing technology. I can point to anecdotal evidence of millions of people who are neither idiots nor liars, but atheist apologists say this is of no value. This is unreasonable of them, but it is not the main problem with their objection to theistic belief.

The objection is misconceived at the outset. The demand for scientific proof of God derives from the idea (highly contentious) that everything is amenable to empirical or scientific inquiry. This may be true of everything in what is generally called the “natural world”, but the appropriate scope of a conversation about whether or not God exists is all of reality, not just the natural world. No-one has established that they are the same and there is no reason to assume that they are.

If I were somehow impartial on the subject (I can’t really pretend to be), I would observe that the atheists have rejected the theistic “delusion” and replaced it with an unproved assumption. And remark that this is not an intellectual advance.

Insistence on evidence limits the scope of the discussion about God, which falsely (and unfairly) loads the discussion towards no-God. God’s existence isn’t the kind of [alleged] fact that can be investigated empirically or scientifically.

I appreciate that science is indispensable and authoritative for inquiring into the natural world. And I understand why science-minded atheists might feel uneasy venturing into a discussion in which their scientific tools are of no use. However, the scope of the discussion should not be dictated by their methodology or convenience.

There is more directly analytical way of approaching the topic. The scientific (or “empiricist” or “materialist”) world-view is based on the following principle:

It is reasonable to believe that a statement is true (including a statement about something existing) only if the truth of the statement is proved empirically (ie by “evidence”). It is reasonable to believe a statement might be true only if its truth is provable (at least potentially) empirically.

I’ve done my best to represent the position correctly and fairly. The second sentence is added to accommodate the fact that science is still learning and, in honest hands, doesn’t make absolute claims about facts and knowledge.

The typical atheist believes the above statement of principle to be true. The truth of the statement has not been proved empirically. Nor is its truth provable empirically. The truth of the statement is assumed.

It is this statement which appears to give rise to the assumption that reality consists entirely of the natural world – amenable to empirical observation (or scientific inquiry).

Most people, probably everyone, have a starting-point in their thinking – a starting-point from which they proceed forward and outward. They aren’t necessarily aware of it. My starting-point is God. The typical atheist’s is the above statement. You can discover someone’s starting-point by asking “Why?”. Whatever the topic, if you keep asking “Why?”, you will find yourself delving more deeply into the other person’s thinking, layer by layer and, when you no longer get a different answer, you’ve reached their starting-point. I’ll end with “Because of God” or “Because God is God”, or similar.

There is a serious logical advantage to the starting-point of God: I take a leap of faith to God and always acknowledge that I’ve done so, so my thinking is consistent. The atheist takes a leap of faith (to the truth of the above statement) and, from that moment, scorns leaps of faith. That sequence of thought is profoundly inconsistent, indeed arguably “irrational”.

I am not arguing here for the existence of God (or anything else supernatural), much less against science. I am identifying and critiquing the assumption that reality consists only of the natural world. This assumption involves locking one’s mind inside an “empiricist box” and believing that, because it’s a very large box (as vast as the natural world), it’s not a box at all. This box represents a self-imposed and arbitrary limitation on reality and one’s ability to apprehend it.

The empiricist box is no place to find out whether or not God exists. Even if reality does consist only of the natural world, this will not be discovered inside the box. To think outside such a commodious box might seem like a lot to ask, but a serious God inquiry has to be seriously intrepid.

No-one likes their assumptions being challenged, or even exposed. There was a time when a person like me could safely assume “the other person” believed in God as much as I do. That would be a while back. I’ve had to learn to mingle and discuss far away from this comfort zone.

Being only human, atheists and other sceptics also relish intellectual and social comfort. I can’t help but think the empiricist box is a place of refuge for the sceptic. Atheists are not all as triumphant and disdainful, or even as confident, as their public apologists. Besides, most sceptics are not atheists at all, they just “don’t know”: many are actually curious, while many others find the subject of God exhausting or frustrating, or embarrassing. Many others, of course, are simply not interested.

Because it is superficially impressive, the empiricist argument provides a pretext for dismissing religious claims on reflex and for not pursuing any genuine curiosity about God.

The argument is actually misconceived and irrelevant, which is a problem for those many atheists who value intellectual integrity and would like their disbelief to have a sound foundation.

by NZ Christian Network | 13 Aug , 2014 | FOCUS, Secularism

Here’s an interesting post written by Nury Vittachi and found on the Science 2.0 website. Nury writes from a multi-faith perspective… He lives and works in China, and is surrounded by different ways of thinking (his mother is Buddhist, father Muslim, wife Christian, and China is atheist by law). Nury writes science and history books for young people (publishers include Scholastic) and was once short-listed for a minor sci-fi prize for a children’s book he wrote on relativity. His range of interests include particle physics and quantum mechanics.

Metaphysical thought processes are more deeply wired than hitherto suspected

WHILE MILITANT ATHEISTS like Richard Dawkins may be convinced God doesn’t exist, God, if he is around, may be amused to find that atheists might not exist.

Cognitive scientists are becoming increasingly aware that a metaphysical outlook may be so deeply ingrained in human thought processes that it cannot be expunged.

While this idea may seem outlandish—after all, it seems easy to decide not to believe in God—evidence from several disciplines indicates that what you actually believe is not a decision you make for yourself. Your fundamental beliefs are decided by much deeper levels of consciousness, and some may well be more or less set in stone.

This line of thought has led to some scientists claiming that “atheism is psychologically impossible because of the way humans think,” says Graham Lawton, an avowed atheist himself, writing in the New Scientist. “They point to studies showing, for example, that even people who claim to be committed atheists tacitly hold religious beliefs, such as the existence of an immortal soul.”

This shouldn’t come as a surprise, since we are born believers, not atheists, scientists say. Humans are pattern-seekers from birth, with a belief in karma, or cosmic justice, as our default setting. “A slew of cognitive traits predisposes us to faith,” writes Pascal Boyer in Nature, the science journal, adding that people “are only aware of some of their religious ideas”.

INTERNAL MONOLOGUES

Scientists have discovered that “invisible friends” are not something reserved for children. We all have them, and encounter them often in the form of interior monologues. As we experience events, we mentally tell a non-present listener about it.

The imagined listener may be a spouse, it may be Jesus or Buddha or it may be no one in particular. It’s just how the way the human mind processes facts. The identity, tangibility or existence of the listener is irrelevant.

“From childhood, people form enduring, stable and important relationships with fictional characters, imaginary friends, deceased relatives, unseen heroes and fantasized mates,” says Boyer of Washington University, himself an atheist. This feeling of having an awareness of another consciousness might simply be the way our natural operating system works.

Read the full post on Science 2.0

I’ve decided now to refer to “non-theists”, as non-belief in God ranges from frank atheism (“There is no God”) to agnosticism (“I don’t know”) with each position having its own spectrum and labels not being applied consistently. Non-theists sometimes describe themselves as “rationalists”, “realists”, “sceptics”, “humanists” or “secularists”. However, they all reside in the “empiricist box” (see Part 1).

I’ve decided now to refer to “non-theists”, as non-belief in God ranges from frank atheism (“There is no God”) to agnosticism (“I don’t know”) with each position having its own spectrum and labels not being applied consistently. Non-theists sometimes describe themselves as “rationalists”, “realists”, “sceptics”, “humanists” or “secularists”. However, they all reside in the “empiricist box” (see Part 1). On the other hand, “I don’t know” is often a cover for “I don’t care”. It seems strange not to care that there might be Someone who made the cosmos and is in touch with humanity, but we continue to hear “I’ll cross that bridge when I get to it”.

On the other hand, “I don’t know” is often a cover for “I don’t care”. It seems strange not to care that there might be Someone who made the cosmos and is in touch with humanity, but we continue to hear “I’ll cross that bridge when I get to it”. At risk of stating the obvious, a conversation with a non-theist is not a conversation with the embodiment of some ideas but with a fabulously complex and unique human being who is in God’s image and likeness, is loved by God, is in humanity’s shared predicament and has an irrefutable claim on everyone’s love.

At risk of stating the obvious, a conversation with a non-theist is not a conversation with the embodiment of some ideas but with a fabulously complex and unique human being who is in God’s image and likeness, is loved by God, is in humanity’s shared predicament and has an irrefutable claim on everyone’s love.

Moral relativism

Moral relativism