Atheism is not all it’s cracked up to be – part 2

‘Morality and the human being‘ is the second part in the Atheism is not all it’s cracked up to be series by Gavan O’ Farrell, who works as a public sector lawyer.

‘Morality and the human being‘ is the second part in the Atheism is not all it’s cracked up to be series by Gavan O’ Farrell, who works as a public sector lawyer.

Part one can be read here: Reason and Evidence

MORALITY AND THE HUMAN BEING

Atheists say that Christians often accuse them of being wicked. Such an accusation (which I’ve personally never heard in New Zealand) is not only rude but false: it is quite apparent that many atheists are very moral people.

However, this is despite their atheism. I say this because I suggest that atheists cannot explain their morals. The morals of virtually all atheists are inherited from Christianity – especially the very basic ideas that human beings are highly (and equally) significant.

After all, New Zealand’s secularism is post-Christian: it didn’t arrive out of the blue, like a baby delivered by a stork. Like a real baby, it was generated organically and possesses inherited traits.

Moral relativism

Moral relativism

Most atheists say they are moral relativists, who believe there are no “objective” moral requirements that apply to everyone. For them, what we think is an objective morality is just the set of moral constructs developed by our society. Other societies have theirs too and it is impossible to judge another society, no matter what it does, because there is no objective global standard. Many moral relativists go further and say that relativism operates at the individual level: “my morality and my right/wrong” vs “your morality etc”.

As I understand it, moral relativism has long been discredited in philosophical circles. For example, when they promote “tolerance” of other views as being immune from criticism, they insist on this tolerance as an absolute requirement – which contradicts their whole position.

In addition, relativism doesn’t capture the reality of moral discourse. When two people disagree about a moral question, their views are in conflict. However, if two relativists “disagree”, their views don’t conflict because they’re describing their respective moral feelings about the topic, not the moral character of the topic itself (because it has no objective moral character). Their “disagreement” is like A and B discussing headaches, with A saying “I have a headache” and B replying “Well, I don’t have a headache”.

Anyhow, I have found that people who call themselves relativists don’t really seem to mean it. They use it to ward off criticism directed at them: “That’s just your right and wrong (etc)”. But, when they criticise others, they tend to speak very dogmatically, as though there is an objective standard (which they don’t explain).

It is tempting to disdain relativism, but it remains important because a large number of people nominally subscribe to it.

Objective secular morality

Some atheists do acknowledge that morality consists of objective rules, or at least principles, that apply to every individual and every society.

Evolved morality:

Some atheists believe that basic “moral” behaviours (eg altruism) evolved in order for societies (or humanity itself) to survive.

I accept evolution, but it just “happens”, it doesn’t give value and has no authority. We don’t obey moral rules (eg behave altruistically) just because we find them in our midst. We need a reason to obey them.

If we are urged to obey for the sake of the survival of humanity, we can still ask why humanity “should” survive. There is an epic urge to survive, but this is different from “should”. Especially nowadays, when some say we shouldn’t survive because of the harm we’ve caused to the environment.

Deduced morality:

Other atheists try to develop an objective secular morality from the ground up.

Consequentialism:

This approach to morality says an action is right or wrong according to its consequences. However –

- By speaking of good and bad consequences, this approach again assumes certain values (eg survival or well-being) and just imposes them. Besides, whose well-being are we supposed to value, and why? Just humans? All humans?

- Consequentialism rests on the idea that the ends justify the means, and we all know how ruthless and dangerous that can be.

- A consequentialist moral rule is only a rule-of-thumb. If lying is morally wrong because it usually does more harm than good, I must still decide what my specific intended lie will cause.

- I can only consider the foreseeable consequences: the actual consequences are yet to occur. A consequentialist can’t judge an action until afterwards. We need to know beforehand!

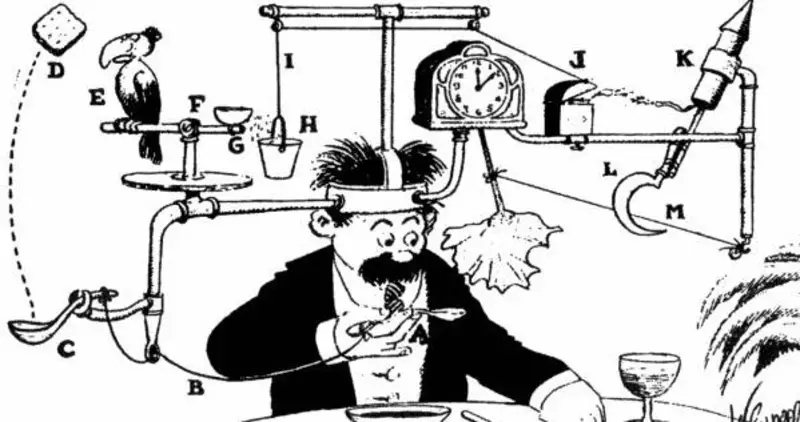

- And my decision could take ages. Every action has myriad consequences that go forever. This is unworkable.

- Workable or not, any rules emerging from consequentialism are made by human beings. I end up being completely subject to majority rule. We know the majority can be wrong, which reminds us that the majority has power, not moral authority.

- Consideration of consequences is an important element of moral decision-making, but it’s not all there is to it.

Positivism:

The alternative approach is “positivism”: the rules identify behaviour that is considered to be inherently right or wrong. EG lying is inherently wrong, wrong by its nature, no calculations are needed. This is more realistic and workable as it relies on an intuitive repugnance for lying rather than a remote sense that the lie might do more harm than good.

However, secular positivism also assumes values and also subjects us to the dubious moral authority of the majority.

The human being:

When all the theorising about morality is done, nothing beats a rich definition of the human being as a reason for us behaving well towards each other.

However, relying on “the evidence”, the atheist tells us that human beings are no more than the latest gorilla upgrade, the planet’s most complex organism and top predator and that each of us is a mixed bag of kindness and malice. If this is all a human is, it makes equal sense to hate them as to love them.

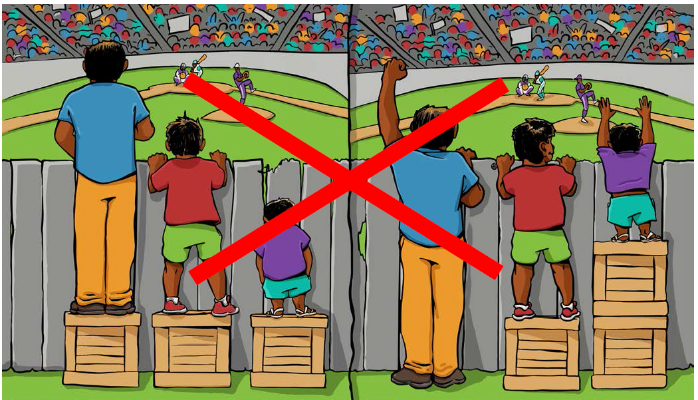

Atheists talk about justice because they believe in equality. Good, but the evidence says people are not equal: many differences are socially constructed, but there are also real inherent superiorities (eg intelligence, strength, agility, prowess, disposition).

We Christians believe each human being to be extremely significant and equally so, regardless of other characteristics, because we are made in God’s image and likeness. This Imago Dei is the trump card. Loving people and giving them justice makes immediate sense because of what they are: a human being demands love and justice simply by being a human being.

Secularists reject all this, of course, and have not yet identified (or even imagined) anything lovable to replace it. The basics of post-Christian secular morality are really a memory of Christianity.

Afterthought

It may be that the atheists’ difficulty in explaining the value of the individual human being has helped give rise to the new ethos, identity politics. While this ethos pays lip-service to “human rights”, it has actually moved well away from the idea of valuing each person individually. Identity politics sees only groups.

Groups are certainly important, but only because they are groups of individual human beings: the value of the group is the result of simple arithmetic.

Identity politics doesn’t get this. After all, it creates the groups – herds, really. Identity politics displays the astonishing arrogance of beholding a spectacularly complex and unique human being and allocating them to a herd by reference to a handful of characteristics (sex, “gender”, sexual orientation, race). So much about each person is simply ignored! Then the herders tell us which herd is “good” and which is “bad”.

Identity politics is spurious, of course, but it must be taken seriously because it has become so powerful (and dangerous). While many atheists are on the political Left, the more serious among them may have to break ranks from identity politics in due course, for the sake of intellectual integrity.