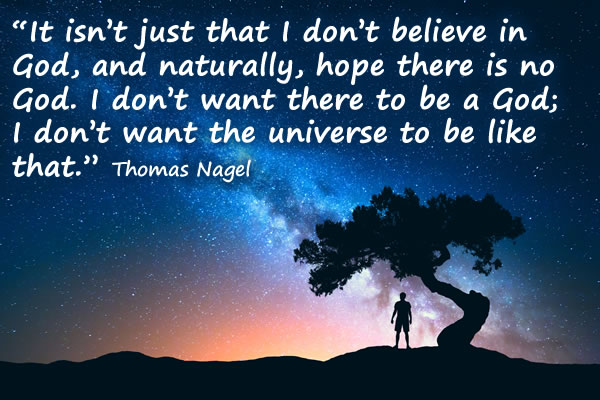

“I don’t want it, so it isn’t there!” is the third part in the Atheism is not all it’s cracked up to be series by Gavan O’ Farrell, who works as a public sector lawyer.

Part one can be read here: Reason and Evidence

Part two can be read here: Morality and the Human Being

“I don’t want it, so it isn’t there!”

So far, this series on atheism has discussed whether we theists are “irrational” (Part 1) and whether morality is viable without God (Part 2).

I’ll now briefly canvas some of the other things atheists often say.

Two seemingly peripheral arguments

“Which religion?”: A common reason for rejecting God seems to be: “There are thousands of religions, most of them mutually incompatible, they can’t all be true.”

You’d have to look hard to find “thousands”. Anyway, however many there are, my response is “If you are curious, you will do the work of inquiring, just as a serious scientist does when faced with a difficult and complex natural question. If you are not curious, or not willing to do the work, just say so”.

This atheist assertion insinuates, “Religions can’t all be true, so none of them are”, which is clearly illogical: one of them could be true, the atheist just doesn’t know which one. The pervasiveness of theistic belief (globally and throughout history) should really make a genuine sceptic curious.

The “onus of proof”: You will often hear atheists say it is up to theists to prove God’s existence. This made better sense when Christians were doing the talking while the atheists just appraised the arguments.

This has changed, atheists now make a positive assertion “You may not claim a fact unless there is empirical/scientific proof of that fact”. They are now on the front foot, pushing their [limited and limiting] theory of knowledge.

We do wish to persuade about God, but it’s not a matter of “proof” (see Part 1). As I understand the dynamics, we Christians commend our faith to others. I haven’t noticed any Christians insisting on belief in God – not recently, anyway. By contrast, atheists insist that it is only permissible to talk facts (including facts about God) if those facts are proved empirically/scientifically. This insistence swings the onus of proof onto them: they may no longer assume this view and impose it, they must establish it.

It is worth remarking that the location of the onus of proof has no bearing on the issue of whether or not God exists: it’s just a discussion protocol.

I mention these arguments, not because they are intrinsically important but because they come up so frequently. They have negligible logical value as arguments. Really, they seem to me to be excuses rather than arguments – attempted justification for not believing and for not being inquisitive. Another refuge, like the “empiricist box” (Part 1).

It won’t hurt us to acknowledge that not wanting God to exist is entirely understandable. We all value our autonomy and we’re all at least half-inclined to resent authority. Even faith (a shifting, moody thing) is not a 24-7, airtight defence against this.

I wouldn’t be surprised if simply not wanting God to exist turned out to be the central point. And, to the extent that we Christians can empathise, a meeting-point.

“Christianity is not ‘good news’ but bad news”

Atheists often say Christianity is evil and offer a bundle of “proofs” which have become familiar – war, forced conversion, the Spanish Inquisition, witch-hunting, tolerance of slavery, the oppression of women and gays, the suppression of science and, more recently, protected paedophilia. To this list might be added Old Testament violence and the “immoral” nature of Redemption by Christ’s death.

Sometimes, atheists add that they would refuse to worship a God who is behind all of this – a strange assertion that wants to sound heroic but can’t possibly be if there is no God.

Atheists should hesitate before offering moral judgements (see Part 2) but, on the other hand, we Christians should not rely on this to avoid discussion of wrongs we know the Church has done. After all, the Church consists largely of human beings and has wielded enormous power – a notoriously dangerous combination. For the most part, though, the proofs rely on the hasty acceptance of information that is skewed or incomplete.

Christianiy’s track record is critical to the plausibility of Christianity because it is difficult to recommend Christ if history shows that accepting this recommendation is a bad idea. In Part 4, I’ll mention some books that help set our track record straight.

The dark side of this track record is also another excuse for not being inquisitive, this time about Christianity. After all, atheists don’t seem to consider the possibility that God might also be appalled at some things the Church has done.

The attack on Redemption is a separate matter, and is entirely misconceived. Our critics liken it to the ancient ritual of “scapegoating”, where a village would seize a goat, load it up with paraphernalia representing the village’s sins and drive it into the desert so that the sins (and the goat) are never seen again.

We believe Christ volunteered to, so to speak, “carry our sins into the desert”, that He did this long ago without any urging from you or me, that He returned in excellent condition and that He now asks us whether the sins He bore included ours. We say Yes, not to be cruel, but out of common sense and awe-struck gratitude. It would be unspeakably stupid to say No.

0 Comments