A universal mission

Pentecost is a good moment to take a reality check concerning any lurking idolatry of nationalism in our hearts.

The events described by Luke in the opening chapters of The Acts of the Apostles remind us that the end goal of God’s purposes in human history is the ingathering of a multi-ethnic global church: ‘from every tribe, language, people and nation’, as John writes in his Revelation (5:9).

The outpouring of the Spirit birthed this ‘rainbow’ church when Jews and converts, including Cretans and Arabs, from ‘every nation under heaven’, heard the disciples praising God in the languages of their lands of residence. So Peter stood up to explain that what everyone was witnessing was what the prophet Joel had foretold would happen in ‘the last days’.

Clearly we have been in the last days therefore ever since Pentecost. Also clearly, this was only the start of the fulfilment of this prophecy. The Spirit is yet to be poured out on all flesh. There is still much more to come–something that should excite us.

It should also caution us against the sort of religious nationalism being preached from political platforms on both sides of the Atlantic these days. We live somewhere between Acts chapter 2 and Revelation chapter 5, as part of the process of a church becoming increasingly multi-cultural. The New Jerusalem will be multi-racial and multi-lingual, all focused on the One who will reconcile all things under heaven and on earth.

Inclusive

Yet too often we see believers making the same mistake for which Israel was rebuked by the prophets and by Jesus himself: ethno-centrism. Instead of embracing God’s purposes for all peoples, Israel focused too often on being the Chosen. Too often they adopted an ‘Israel first’ policy. But they forgot what they had been chosen for: to bless all the peoples of the world, and be a light to the peoples.

Here is a sober warning for those tempted to embrace a religious nationalism ‘to preserve our Christian heritage’. The gospel is inclusive, intended for all peoples. It is not the exclusive right of westerners. We are better people when we commit to the welfare of others, that is to ‘loving our neighbours’. We are better nations when we promote the common good of the community of nations, not an ethnic nationalism which places one nation over others as a political goal.

As Christians, we strive to follow the exclusive claims of the gospel. Yet those of us living in countries shaped by Christianity–Orthodox, Catholic or Protestant–often assume that the marriage of faith and nationalism is good and biblical. For ‘Christian nationalism’ has roots back in the Constantinian conversion of Rome to Christianity, or even further to the Old Testament covenant between God and Israel. At different stages of history, Christians have claimed a ‘divine instrument’, ‘manifest destiny’, or ‘light to the nations’ calling–from Constantine’s Roman Empire through to Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire, Holy Orthodox Russia, Britain versus Spain, Afrikaners in South Africa and the United States.

Catholics are generally less vulnerable than Protestants to the temptations of a ‘God and country’ mentality, being conscious of belonging to a ‘catholic’ (meaning ‘universal’) Church, rather than identifying with one particular nation like the Church of England or the Dutch Reformed Church. And yet today in Catholic nations like Hungary, Poland and Italy, religious nationalism threatens to further undermine the foundations of free and open society in the name of ‘preserving our Christian heritage’.

Chaplain

Eastern Orthodox Churches however tend to closely identify with their ethnic nationalities: Greek Orthodox, Serbian Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, Romanian Orthodox, Bulgarian Orthodox, Ukrainian Orthodox, and so on. Church-state relations in the Orthodox world have

always be based on the concept of symphonia or harmony, which often meant the church became the chaplain rather than prophet to the state.

Too often we assume nations have always been around and are the God-designed unit of human community. We quote Acts 17:26 about God having ‘made from one man every nation of mankind to live on the face of the earth, having determined their appointed times and the boundaries of their lands.’ But nation-states as we see them on our world map today are recent developments, as opposed to ethne (peoples), the word used in Acts 17. The French Revolution set off a wave of nationalism across Europe sparking revolutions which still continue to affect this continent. The twentieth century has been described as ‘a century of nations and nationalism’, a ‘bloody religion whose victims dwarf in number the casualties of the crusades’, ‘a reaction against historic Christianity, against the universal mission of Christ’.

Pentecost emboldened the disciples to declare to the authorities: ‘We must obey God rather than men’ (Acts 5:29). May the Spirit embolden us also to stand for truth, love and justice, and for God’s purposes for all peoples.

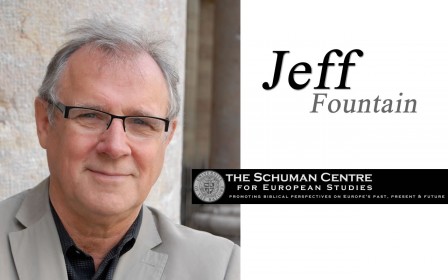

Jeff Fountain is director of the Schuman Centre for European Studies, affiliated with the University of the Nations. Originally from New Zealand, Jeff has lived in Europe for 38 years and carries a Dutch passport. He was director of Youth With A Mission Europe for 20 years and chairs the Hope For Europe Round Table. Jeff writes an email column called Weekly Word and has written several books including Living as People of Hope and Deeply Rooted.